AI in Society

Opinions and positions expressed in this blog are mine, and do not represent my employer's opinions or positions.

Search This Blog

Wednesday, May 21, 2025

Executive Cognition, a New Learning Outcome We Cannot Ignore

Tuesday, May 13, 2025

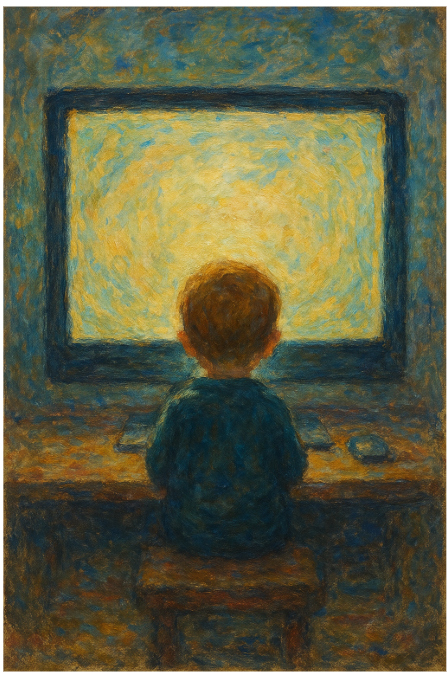

When Smart People Oversimplify Research: A Case Study with Screen Time

"I think we have just been going through a catastrophic experiment with screens and children and right now I think we are starting to figure out that this was a bad idea."

This claim from Klein's recent conversation with Rebecca Winthrop is exactly the kind of statement that makes for good podcasting. It is confident, alarming, and seemingly backed by science. There is just one problem: the research on screen time and language development is not nearly as straightforward as Klein suggests.

Let us look at what is likely one of the studies underlying Klein and Winthrop's claims – a recent large-scale Danish study published in BMC Public Health by Rayce, Okholm, and Flensborg-Madsen (2024). This impressive research examined over 31,000 toddlers and found that "mobile device screen time of one hour or more per day is associated with poorer language development among toddlers."

Sounds definitive, right? The study certainly has strengths. It features a massive sample size of 31,125 children. It controls for socioeconomic factors. It separates mobile devices from TV/PC screen time. It even considers home environment variables like parental wellbeing and reading frequency.

So why should we not immediately conclude, as Klein does, that screens are "catastrophic" for child development?

Here is what gets lost when research travels from academic journals to podcasts: The authors explicitly state that "the cross-sectional design of the study does not reveal the direction of the association between mobile device screen time and language development." Yet this crucial limitation disappears when the research hits mainstream conversation.

Reverse causality is entirely possible. What if children with inherent language difficulties gravitate toward screens? What if struggling parents use screens more with children who are already challenging to engage verbally? The study cannot rule this out, but you would never know that from Klein's confident proclamation.

Hidden confounders lurk everywhere. The study controlled for obvious variables like parental education and employment, but what about parenting style? Quality of interactions? Temperamental differences between children? Parental neglect? Any of these could be the real culprit behind both increased screen time AND language delays.

The nuance gets nuked. The research found NO negative association for screen time under one hour daily. Yet somehow "moderation might be fine" transforms into "catastrophic experiment" in public discourse.

Klein is no dummy. He is one of America's sharpest interviewers and thinkers. So why the oversimplification?

Because humans crave certainty, especially about parenting. We want clear villains and simple solutions. "Screen time causes language delays" is a far more psychologically satisfying narrative than "it is complicated and we are not sure."

Media figures also face incentives to present clean, compelling narratives rather than messy nuance. "We do not really know if screens are bad but here are some methodological limitations in the current research" does not exactly make for viral content.

The next time you hear a confident claim about screens (or anything else) backed by "the research," remember: Correlation studies cannot prove causation, no matter how large the sample. Most human behaviors exist in complex bidirectional relationships. The most important confounding variables are often the hardest to measure. Journalists and podcasters simplify by necessity, even the brilliant ones. Your intuition toward certainty is a psychological quirk, not a reflection of reality.

Screens may indeed have negative effects on development. Or they might be mostly benign. Or it might depend entirely on content, context, and the individual child. The honest answer is we do not fully know yet – and that is precisely the kind of nuanced conclusion that rarely makes it into our public discourse, even from the smartest voices around.

When it comes to AI – the current technological bogeyman – we have even less to go on. We have very little empirical evidence about AI's effects on human development, and almost none of it qualifies as good quality evidence. It is way too early to make any kind of generalizations about how AI may affect human development.

What we do know is the history of technological panics, and how none of them ever fully materialized. Television was going to rot our brains. Video games were going to create a generation of violent sociopaths. Social media was going to destroy our ability to concentrate. And yet, no contemporary generation is stupider than their parents – that we know for sure. Neither TV nor computer games made us stupider. Why would AI be an exception?

Each new technology brings genuine challenges worthy of thoughtful study. But between rigorous research and knee-jerk catastrophizing lies a vast middle ground of responsible, curious engagement – a space that our public discourse rarely occupies.

Friday, May 2, 2025

AI Isn't Evolving as Fast as Some Thought

It is not the most popular opinion, but it deserves to be said out loud: the technology behind large language models hasn’t fundamentally changed since the public debut of ChatGPT in late 2022. There have been improvements, yes—more parameters, better fine-tuning, cleaner interfaces—but the underlying mechanism hums along just as it did when the world first became obsessed with typing prompts into a chat window and marveling at the answers. The much-promised “qualitative leap” hasn’t materialized. What we see instead is refinement, not reinvention.

This is not to deny the impact. Even in its current form, this technology has triggered innovation across industries that will be unfolding for decades. Automation has been democratized. Creatives, coders, analysts, and educators all now work with tools that were unthinkable just a few years ago. The breakthrough did happen—it just didn’t keep breaking through.

The essential limitations are still intact, quietly persistent. Hallucinations have not gone away. Reasoning remains brittle. Context windows may be longer, but genuine comprehension has not deepened. The talk of “AGI just around the corner” is still mostly just that—talk. Agents show promise, but not results. What fuels the uber-optimistic narrative is not evidence but incentive. Entire industries, startups, and academic departments now have a stake in perpetuating the myth that the next paradigm shift is imminent. That the revolution is perennially just one release away. It is not cynicism to notice that the loudest optimists often stand to benefit the most.

But let’s be fair. This plateau, if that’s what it is, still sits high above anything we imagined achievable ten years ago. We’re not just dabbling with toys. We’re holding, in our browsers and apps, one of the most astonishing technological achievements of the 21st century. There’s just a limit to how much awe we can sustain before reality sets in.

And the reality is this: we might be bumping up against a ceiling. Not an ultimate ceiling, perhaps, but a temporary one—technical, financial, cognitive. There is only so far scaling can go without new theory, new hardware, or a conceptual shift in how these systems learn and reason. The curve is flattening, and the hype train is overdue for a slowdown. That does not spell failure. It just means it is time to stop waiting for the next miracle and start building with what we have already got.

History suggests that when expectations outpace delivery, bubbles form. They burst when the illusion breaks. AI might be heading in that direction. Overinvestment, inflated valuations, startups without real products—these are not signs of a thriving ecosystem but symptoms of a hype cycle nearing exhaustion. When the correction comes, it will sting, but it will also clear the air. We will be left with something saner, something more durable.

None of this diminishes the wonder of what we already have. It is just a call to maturity. The true revolution won’t come from the next model release. It will come when society learns to integrate these tools wisely, pragmatically, and imaginatively into its fabric. That is the work ahead—not chasing exponential growth curves, but wrestling with what this strange, shimmering intelligence means for how we live and learn.

Thursday, April 24, 2025

An Executive Order That Misses the Point

There’s something oddly familiar about President Trump’s latest executive order on AI in education. It arrives with the usual pomp—task forces, public-private partnerships, shiny language about national competitiveness. It nods to professional development, student certifications, and the holy grail of “future readiness.” And yet, beneath the surface, it offers little that addresses the real crisis: the profound, structural disruption AI has already begun to unleash on the educational system.

At first glance, the executive order seems like a step in the right direction. Who would argue against preparing students for an AI-dominated future? The task force will do what task forces do: coordinate. Teachers will receive grants for AI training, and students might get badges or certificates that proclaim them “AI literate.” It all sounds terribly forward-thinking. But there’s a strange emptiness to the plan, like training firefighters to use a new hose while the forest burns around them.

What the order fundamentally fails to grasp is not that AI is coming—it’s that AI is already here, and it has changed everything. The real problem is not a lack of exposure to AI tools, but the complete misalignment between existing educational structures and the cognitive shift AI demands. This isn't a matter of professional development. It’s a matter of epistemology. What we teach, how we assess, and the very roles of teachers and students—these are all in flux.

A truly meaningful policy would start not with a national challenge or another conference keynote, but with funding for large-scale curriculum realignment. AI doesn’t just add another subject; it changes the assumptions under which all subjects are taught. Writing, for instance, is no longer merely a human-centered exercise in articulation—it is now entangled with generative tools that can produce text faster than students can think. The same is true for coding, design, even problem-solving. If students are using AI to generate answers, then we need to redesign assignments to emphasize process over product, collaboration over output, judgment over memorization. That’s not a tweak—it’s a reinvention.

And teachers? They're not just under-trained; they’re overwhelmed. They’re being asked to both maintain continuity and facilitate transformation, to adopt AI while resisting its most corrosive effects. Without time, resources, and genuine structural support, this is educational gaslighting: expecting miracles with nothing but webinars and a cheerful press release.

It would be tempting to chalk this up to Trumpian optics—another performance of leadership without the substance. But the failure runs deeper than that. The Biden administration, for all its technocratic polish, missed the mark too. There has been a bipartisan inability to understand the core disruption AI poses to education. This is not about helping kids “catch up” in reading and math. It is about redefining what catching up even means in a world where machines do much of the thinking.

The deeper pattern is this: a long-term habit of reforming education without understanding it. Policymakers continue to treat education as if it were a content delivery mechanism, easily reprogrammed for the next industrial wave. But education is not a transmission line—it’s an ecosystem of meaning, motivation, and identity. AI does not simply slot into that ecosystem. It changes its climate.

If the United States genuinely wants to lead in an AI-driven world, then it must do more than produce AI-savvy workers. It must invest in educators not as functionaries, but as architects of a new pedagogical order. That takes courage, not just coordination. It takes money, not just mandates.

So yes, the executive order is headed in the right direction. But it’s moving far too slowly, and on the wrong road.

Thursday, April 17, 2025

Why Education Clings to Irrelevance

There’s a particular irony in the way schools prepare us for life by arming us with tools designed for a world that no longer exists. Latin, long dead yet stubbornly alive in syllabi. Algebra, elegantly abstract but only marginally helpful in daily decisions compared to statistics, which might actually help you not get swindled by a mortgage. Even now, when artificial intelligence knocks at the schoolhouse door, the impulse is to double down on handwriting and closed-book tests, as if graphite and paranoia can hold off the machine age.

The problem isn’t just inertia. It’s something deeper—almost spiritual. Education doesn’t merely lag behind practicality. It seems to celebrate its irrelevance. Irrelevance isn’t a bug of the system. It’s the feature. Like a stubborn elder at the dinner table insisting that things were better “back in the day,” the institution of education resists change not just because it can, but because its authority is rooted in not changing.

To teach is, implicitly, to claim authority. But where does this authority come from? Not the future—that’s terra incognita. You can't be an expert in what hasn't happened yet. So the educator turns to the past, because the past has already been canonized. It has textbooks. It has footnotes. It has certainty. And nothing flatters the authority of a teacher more than certainty. Thus, to preserve this role, education must tie itself to a vision of life that is already archived.

There’s a paradox here: education is supposedly preparation for life, yet it often refuses to adapt to the life that is actually unfolding. It is conservative in the truest sense—not politically, but ontologically. It conserves the past. It prepares students for a utopia that once was, or more precisely, that someone once imagined was. The classroom becomes a time capsule, not a launchpad.

This is not entirely wrongheaded. The future is uncertain, and while we might guess at the skills it will demand—data literacy, adaptability, collaborative creativity—we cannot guarantee them. So we retreat to what we can guarantee: the conjugation of Latin verbs, the proof of triangles, the essays written in blue ink. It's a strategy of safety cloaked as rigor. If we can’t foresee what will matter tomorrow, at least we can be very confident about what mattered yesterday.

And yet, this nostalgia has consequences. It breeds irrelevance not just in content, but in spirit. When students ask, “When will I ever use this?” and teachers respond with some forced scenario involving imaginary apples or train schedules, the real answer—“you probably won’t, but we’re doing it anyway”—lurks just beneath the surface. The curriculum becomes a kind of ritual, an educational incense burned in memory of older truths.

The arrival of AI only sharpens this tension. Faced with the destabilizing presence of machines that can write, summarize, solve, and simulate, many educators panic. But rather than adapting, they retreat further. The pencil becomes a moral statement. The closed classroom a sanctuary. There’s almost a theological quality to it, as if real learning must involve a kind of suffering, and anything too efficient is suspect.

It’s tempting to dismiss this all as folly, but maybe it reflects something deeply human. Our fear of irrelevance leads us to preserve what is already irrelevant, in hopes that it might make us relevant again. In this way, education mirrors its creators: creatures of habit, haunted by the past, nervous about the future, and always unsure where real authority should lie.

Perhaps that’s the real lesson schools teach, intentionally or not. That relevance is fragile, and that meaning is something we inherit before we can create it.

Monday, April 7, 2025

Deep Research is still more of a promise

The promise of deep research by AI tools like ChatGPT is simple: feed in a question, receive a nuanced, well-reasoned answer, complete with references and synthesis. And in some domains, it delivers admirably. When it comes to media trends, tech news, or cultural analysis, the tool works best. It sifts through the torrent of online commentary, news articles, blog posts, and social chatter to surface patterns and narratives. The real value here lies not just in the volume of data it processes, but in how the user frames the question. A clever, counterintuitive prompt can elicit insights that feel like genuine thought.

But the illusion shatters when the query turns academic. For scholarly literature reviews, this tool falters. It is not the fault of the software itself—there is no shortage of computational power or linguistic finesse. The limitation is upstream. Most academic journals sit behind expensive paywalls, historically inaccessible to large language models. The corpus they are trained on has lacked precisely the kind of data that matters most for rigorous research: peer-reviewed studies, meta-analyses, theoretical frameworks built over decades.

This, however, is beginning to change. In May 2024, Microsoft signed a $10 million deal with Taylor & Francis to license journal content for its Copilot AI. OpenAI, for its part, has secured a two-year agreement with The Associated Press and forged partnerships with European publishers like Axel Springer, Le Monde, and Prisa Media—giving ChatGPT a better grasp of reputable journalistic and scholarly content. Wiley joined the fray with a $23 million licensing deal to grant an unnamed AI developer access to its academic publishing portfolio. Even Elsevier, long a fortress of paywalled knowledge, is now channeling its scholarly data into AI collaborations.

These are significant moves. They mark a transition from aspiration to access. Once these agreements begin to reflect in AI performance, the quality of output will change markedly. A tool that can both identify the pivotal paper and incorporate it meaningfully into its reasoning would be a true research assistant—something closer to intellectual augmentation than just computational summarization.

It is still early days. Scite, for now, remains stronger at pointing users to the right academic sources, even if its analytical output lacks flair. ChatGPT and its peers, in contrast, excel at synthesis but stumble when the raw material is lacking. The ideal tool is still on the horizon.

There is an irony, nevertheless. AI, the most advanced information-processing technology ever built, has been running on the least rigorous parts of the internet. It has quoted tweets with ease but struggled to cite the peer-reviewed studies that ought to anchor serious inquiry. That is no longer a permanent condition. It is, increasingly, a transitional one.

The future of AI in research will be determined not solely by engineering breakthroughs, but by access negotiations. With major publishers now at the table, the landscape is poised for a shift. For the user, the best strategy remains what it has always been: ask sharp questions. But soon, the machine’s answers may finally rest on deeper knowledge.

Thursday, March 27, 2025

Freeze-Dried Text Experiment

It is like instant coffee, or a shrunken pear: too dry to eat, but OK if you add water. Meet "freeze-dried text" – concentrated idea nuggets waiting to be expanded by AI. Copy everything below this paragraph into any AI and watch as each transforms into real text. Caution: AI will hallucinate some references. Remember to type "NEXT" after each expansion to continue. Avoid activating any deep search features – it will slow everything down. This could be how we communicate soon – just the essence of our thoughts, letting machines do the explaining. Perhaps the textbooks of the future will be written that way. Note, the reader can choose how much explanation they really need - some need none, others plenty. So it is a way of customizing what you read.

Mother PromptExpand each numbered nugget into a detailed academic paper section (approximately 500 words) on form-substance discrimination (FSD) in writing education. Each nugget contains a concentrated meaning that needs to be turned into a coherent text.

Maintain a scholarly tone while including:

• Theoretical foundations and research support for the claims. When citing specific works, produce non-hallucinated real reference list after each nugget expansion.

• Practical implications with concrete examples only where appropriate.

• Nuanced considerations of the concept's complexity, including possible objections and need for empirical research.

• Clear connections to both cognitive science and educational practice.

• Smooth transitions that maintain coherence with preceding and following sections

Expand nuggets one by one, treating each as a standalone section while ensuring logical flow between sections. Balance theoretical depth with practical relevance for educators, students, and institutions navigating writing instruction in an AI-augmented landscape. Wait for the user to encourage each next nugget expansion. Start each Nugget expansion with an appropriate Subtitle

Nuggets

1. Form-substance discrimination represents a capacity to separate rhetorical presentation (sentence structure, vocabulary, organization) from intellectual content (quality of ideas, logical consistency, evidential foundation), a skill whose importance has magnified exponentially as AI generates increasingly fluent text that may mask shallow or nonsensical content.

2. The traditional correlation between writing quality and cognitive effort has been fundamentally severed by AI, creating "fluent emptiness" where writing sounds authoritative while masking shallow content, transforming what was once a specialized academic skill into an essential literacy requirement for all readers.

3. Cognitive science reveals humans possess an inherent "processing fluency bias" that equates textual smoothness with validity and value, as evidenced by studies showing identical essays in legible handwriting receive more favorable evaluations than messy counterparts, creating a vulnerability that AI text generation specifically exploits.

4. Effective FSD requires inhibitory control—the cognitive ability to suppress automatic positive responses to fluent text—paralleling the Stroop task where identifying ink color requires inhibiting automatic reading, creating essential evaluative space between perception and judgment of written content.

5. The developmental trajectory of FSD progresses from "surface credibility bias" (equating quality with mechanical correctness) through structured analytical strategies (conceptual mapping, propositional paraphrasing) toward "cognitive automaticity" where readers intuitively sense intellectual substance without conscious methodological application.

6. Critical thinking and FSD intersect in analytical practices that prioritize logos (logical reasoning) over ethos (perceived authority) and pathos (emotional appeal), particularly crucial for evaluating machine-generated content that mimics authoritative tone without possessing genuine expertise.

7. The "bullshit detection" framework, based on Frankfurt's philosophical distinction between lying (deliberately stating falsehoods) and "bullshitting" (speaking without concern for truth), provides empirical connections to FSD, revealing analytical reasoning and skeptical disposition predict resistance to pseudo-profound content.

8. Institutional implementation of FSD requires comprehensive curricular transformation as traditional assignments face potential "extinction" in a landscape where students can generate conventional forms with minimal intellectual engagement, necessitating authentic assessment mirroring real-world intellectual work.

9. Effective FSD pedagogy requires "perceptual retraining" through comparative analysis of "disguised pairs"—conceptually identical texts with divergent form-substance relationships—developing students' sensitivity to distinction between rhetorical sophistication and intellectual depth.

10. The pedagogical strategy of "sloppy jotting" liberates students from formal constraints during ideation, embracing messy thinking and error-filled brainstorming that frees cognitive resources for substantive exploration while creating psychological distance facilitating objective evaluation.

11. Students can be trained to recognize "algorithmic fingerprints" in AI-generated text, including lexical preferences (delve, tapestry, symphony, intricate, nuanced), excessive hedging expressions, unnaturally balanced perspectives, and absence of idiosyncratic viewpoints, developing "algorithmic skepticism" as distinct critical literacy.

12. The "rich prompt technique" for AI integration positions technology as writing assistant while ensuring intellectual substance comes from students, who learn to gauge necessary knowledge density by witnessing how vague AI instructions produce sophisticated-sounding but substantively empty content.

13. Assessment frameworks require fundamental recalibration to explicitly privilege intellectual substance over formal perfection, with rubrics de-emphasizing formerly foundational skills rendered less relevant by AI while ensuring linguistic diversity is respected rather than penalized.

14. FSD serves as "epistemic self-defense"—equipping individuals to maintain intellectual sovereignty amid synthetic persuasion, detecting content optimized for impression rather than insight, safeguarding the fundamental value of authentic thought in knowledge construction and communication.

15. The contemporary significance of FSD extends beyond academic contexts to civic participation, as citizens navigate information ecosystems where influence increasingly derives from control over content generation rather than commitment to truth, making this literacy essential for democratic functioning.

Your Brain on ChatGPT, a Critique

Looking at this MIT study reveals a fundamental design flaw that undermines its conclusions about AI and student engagement. The researcher...

-

Education has always been, at its core, a wager on the future. It prepares students not only for the world that is, but for the world that m...

-

As someone who remembers using paper maps and phone books, I find myself fascinated by Michael Gerlich's new study in Societies about AI...

-

The relationship between thought and writing has never been simple. While writing helps organize and preserve thought, the specific form wri...