Search This Blog

Wednesday, May 21, 2025

Executive Cognition, a New Learning Outcome We Cannot Ignore

Tuesday, May 13, 2025

When Smart People Oversimplify Research: A Case Study with Screen Time

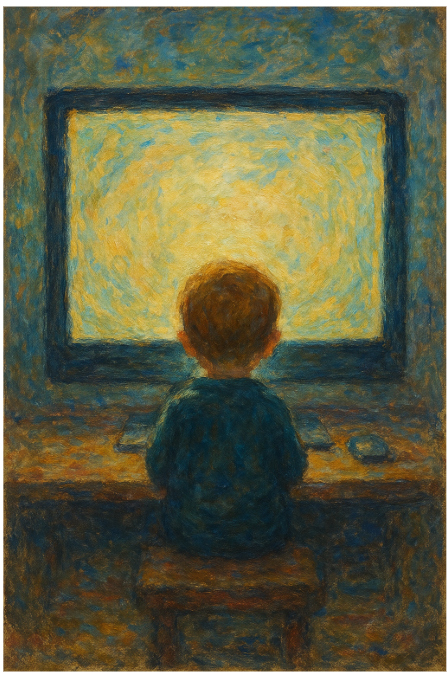

"I think we have just been going through a catastrophic experiment with screens and children and right now I think we are starting to figure out that this was a bad idea."

This claim from Klein's recent conversation with Rebecca Winthrop is exactly the kind of statement that makes for good podcasting. It is confident, alarming, and seemingly backed by science. There is just one problem: the research on screen time and language development is not nearly as straightforward as Klein suggests.

Let us look at what is likely one of the studies underlying Klein and Winthrop's claims – a recent large-scale Danish study published in BMC Public Health by Rayce, Okholm, and Flensborg-Madsen (2024). This impressive research examined over 31,000 toddlers and found that "mobile device screen time of one hour or more per day is associated with poorer language development among toddlers."

Sounds definitive, right? The study certainly has strengths. It features a massive sample size of 31,125 children. It controls for socioeconomic factors. It separates mobile devices from TV/PC screen time. It even considers home environment variables like parental wellbeing and reading frequency.

So why should we not immediately conclude, as Klein does, that screens are "catastrophic" for child development?

Here is what gets lost when research travels from academic journals to podcasts: The authors explicitly state that "the cross-sectional design of the study does not reveal the direction of the association between mobile device screen time and language development." Yet this crucial limitation disappears when the research hits mainstream conversation.

Reverse causality is entirely possible. What if children with inherent language difficulties gravitate toward screens? What if struggling parents use screens more with children who are already challenging to engage verbally? The study cannot rule this out, but you would never know that from Klein's confident proclamation.

Hidden confounders lurk everywhere. The study controlled for obvious variables like parental education and employment, but what about parenting style? Quality of interactions? Temperamental differences between children? Parental neglect? Any of these could be the real culprit behind both increased screen time AND language delays.

The nuance gets nuked. The research found NO negative association for screen time under one hour daily. Yet somehow "moderation might be fine" transforms into "catastrophic experiment" in public discourse.

Klein is no dummy. He is one of America's sharpest interviewers and thinkers. So why the oversimplification?

Because humans crave certainty, especially about parenting. We want clear villains and simple solutions. "Screen time causes language delays" is a far more psychologically satisfying narrative than "it is complicated and we are not sure."

Media figures also face incentives to present clean, compelling narratives rather than messy nuance. "We do not really know if screens are bad but here are some methodological limitations in the current research" does not exactly make for viral content.

The next time you hear a confident claim about screens (or anything else) backed by "the research," remember: Correlation studies cannot prove causation, no matter how large the sample. Most human behaviors exist in complex bidirectional relationships. The most important confounding variables are often the hardest to measure. Journalists and podcasters simplify by necessity, even the brilliant ones. Your intuition toward certainty is a psychological quirk, not a reflection of reality.

Screens may indeed have negative effects on development. Or they might be mostly benign. Or it might depend entirely on content, context, and the individual child. The honest answer is we do not fully know yet – and that is precisely the kind of nuanced conclusion that rarely makes it into our public discourse, even from the smartest voices around.

When it comes to AI – the current technological bogeyman – we have even less to go on. We have very little empirical evidence about AI's effects on human development, and almost none of it qualifies as good quality evidence. It is way too early to make any kind of generalizations about how AI may affect human development.

What we do know is the history of technological panics, and how none of them ever fully materialized. Television was going to rot our brains. Video games were going to create a generation of violent sociopaths. Social media was going to destroy our ability to concentrate. And yet, no contemporary generation is stupider than their parents – that we know for sure. Neither TV nor computer games made us stupider. Why would AI be an exception?

Each new technology brings genuine challenges worthy of thoughtful study. But between rigorous research and knee-jerk catastrophizing lies a vast middle ground of responsible, curious engagement – a space that our public discourse rarely occupies.

Friday, May 2, 2025

AI Isn't Evolving as Fast as Some Thought

It is not the most popular opinion, but it deserves to be said out loud: the technology behind large language models hasn’t fundamentally changed since the public debut of ChatGPT in late 2022. There have been improvements, yes—more parameters, better fine-tuning, cleaner interfaces—but the underlying mechanism hums along just as it did when the world first became obsessed with typing prompts into a chat window and marveling at the answers. The much-promised “qualitative leap” hasn’t materialized. What we see instead is refinement, not reinvention.

This is not to deny the impact. Even in its current form, this technology has triggered innovation across industries that will be unfolding for decades. Automation has been democratized. Creatives, coders, analysts, and educators all now work with tools that were unthinkable just a few years ago. The breakthrough did happen—it just didn’t keep breaking through.

The essential limitations are still intact, quietly persistent. Hallucinations have not gone away. Reasoning remains brittle. Context windows may be longer, but genuine comprehension has not deepened. The talk of “AGI just around the corner” is still mostly just that—talk. Agents show promise, but not results. What fuels the uber-optimistic narrative is not evidence but incentive. Entire industries, startups, and academic departments now have a stake in perpetuating the myth that the next paradigm shift is imminent. That the revolution is perennially just one release away. It is not cynicism to notice that the loudest optimists often stand to benefit the most.

But let’s be fair. This plateau, if that’s what it is, still sits high above anything we imagined achievable ten years ago. We’re not just dabbling with toys. We’re holding, in our browsers and apps, one of the most astonishing technological achievements of the 21st century. There’s just a limit to how much awe we can sustain before reality sets in.

And the reality is this: we might be bumping up against a ceiling. Not an ultimate ceiling, perhaps, but a temporary one—technical, financial, cognitive. There is only so far scaling can go without new theory, new hardware, or a conceptual shift in how these systems learn and reason. The curve is flattening, and the hype train is overdue for a slowdown. That does not spell failure. It just means it is time to stop waiting for the next miracle and start building with what we have already got.

History suggests that when expectations outpace delivery, bubbles form. They burst when the illusion breaks. AI might be heading in that direction. Overinvestment, inflated valuations, startups without real products—these are not signs of a thriving ecosystem but symptoms of a hype cycle nearing exhaustion. When the correction comes, it will sting, but it will also clear the air. We will be left with something saner, something more durable.

None of this diminishes the wonder of what we already have. It is just a call to maturity. The true revolution won’t come from the next model release. It will come when society learns to integrate these tools wisely, pragmatically, and imaginatively into its fabric. That is the work ahead—not chasing exponential growth curves, but wrestling with what this strange, shimmering intelligence means for how we live and learn.

Why Agentic AI Is Not What They Say It Is

There is a lot of hype around agentic AI, systems that can take a general instruction, break it into steps, and carry it through without he...

-

Education has always been, at its core, a wager on the future. It prepares students not only for the world that is, but for the world that m...

-

As someone who remembers using paper maps and phone books, I find myself fascinated by Michael Gerlich's new study in Societies about AI...

-

The relationship between thought and writing has never been simple. While writing helps organize and preserve thought, the specific form wri...